When my fiancé got into bed with me last night he started talking about how he used to tape whole albums off the radio when he was a kid. He got specific. He had to have his mom buy him TDK 90 minute blank tapes—the solid gray ones in the gold wrappers, $2 apiece and sold in packs of five. Maxell was so-so—he would settle for Maxell, but Memorix with its clear tapes and groovy shapes all over was the worst of the worst and he wouldn’t put a single note on that.

He talked about cataloguing the tapes—one album per side. Listening to the DJs talk about the albums and all the music trivia. He still listens to music talk, constantly. He follows about six hundred rock music podcasts and can DJ every song on Sirius with about thirty times the DJ juice as whatever has-been they’ve hired. He is an encyclopedia of rock. Sometimes I’ll turn on classic rock stations that I only marginally like just to give him the opportunity to fan his feathers for me, and it is glorious.

He told me he tried the guitar and piano as a kid because those are the types of instruments a blind kid is supposed to go for, but it wasn’t until someone put him in front of a drum kit that he thought yes…. I can really find my way around here. It all clicked along with the click track and he was a drummer, through-and-through forevermore. He started doing session work in LA by the time he was 14. At 50, he plays in three different bands and bursts out with drum solos on his knees randomly while I’m making dinner, while we’re waiting on an Uber, and even sometimes in the bathroom, (don’t tell him I told you that).

Music, and rock music specifically, and drumming even more specifically than that is the way he makes his way in the world and he has no internal conflict whatsoever about that. I admire that. More than admire: I envy that. More than envy: I am deeply jealous of his soul’s love for its native art. And I wish my soul were that way about writing. It’s getting there, but it has taken a long long time.

Sometimes, when I’m depressed, I find myself doing “depressed” things long before I ever acknowledge I’m depressed. I stop taking care of myself and dressing in nice clothes. I curl up in bed and watch a lot of nostalgia bomb reruns I’ve seen ten thousand times. Walking from room to room makes me tired. I cook the simplest things for dinner—lots of blue box and ramen. But it isn’t until days and days later, when I find myself wrapped up in my blanket cocoon in bed, barely able to move, that I think, “Oh wow. I must be having a depression.”

It’s kind of like that with me and writing.

While Angel was obsessing over TDK vs. Memorex as a kid, I was writing. I wrote my first real poem in the fifth grade and the teacher loved it so much, she posted it in the window for the whole school to see. I still remember it:

The moon is a jagged diamond

Hanging and waiting in suspense

For someone to pluck him from this mine of darkness

That holds him captive

Captive in a sea of stars

That no one dares enter

For fear they’d never return

We were learning about metaphors and similes when I wrote that. I chose metaphor.

I used to ride the bus to school composing poems. As I grew, the poetry onslaught continued. I’d type them on my little Canon electric typewriter that printed a whole line at a time, and put them in packets in the kind of folders you’d put school reports in. I’d give the packets titles and slip them to my teacher on the sly.

I put my poetry in the front cover of my clear-covered three ring binder in high school and changed it out regularly. I wrote down song lyrics from memory and broke the lines apart the way I thought they should be broken.

I wrote satirical pieces in junior high, high school, and college and got in major trouble with teachers and schoolmates over it, but kept doing it anyway.

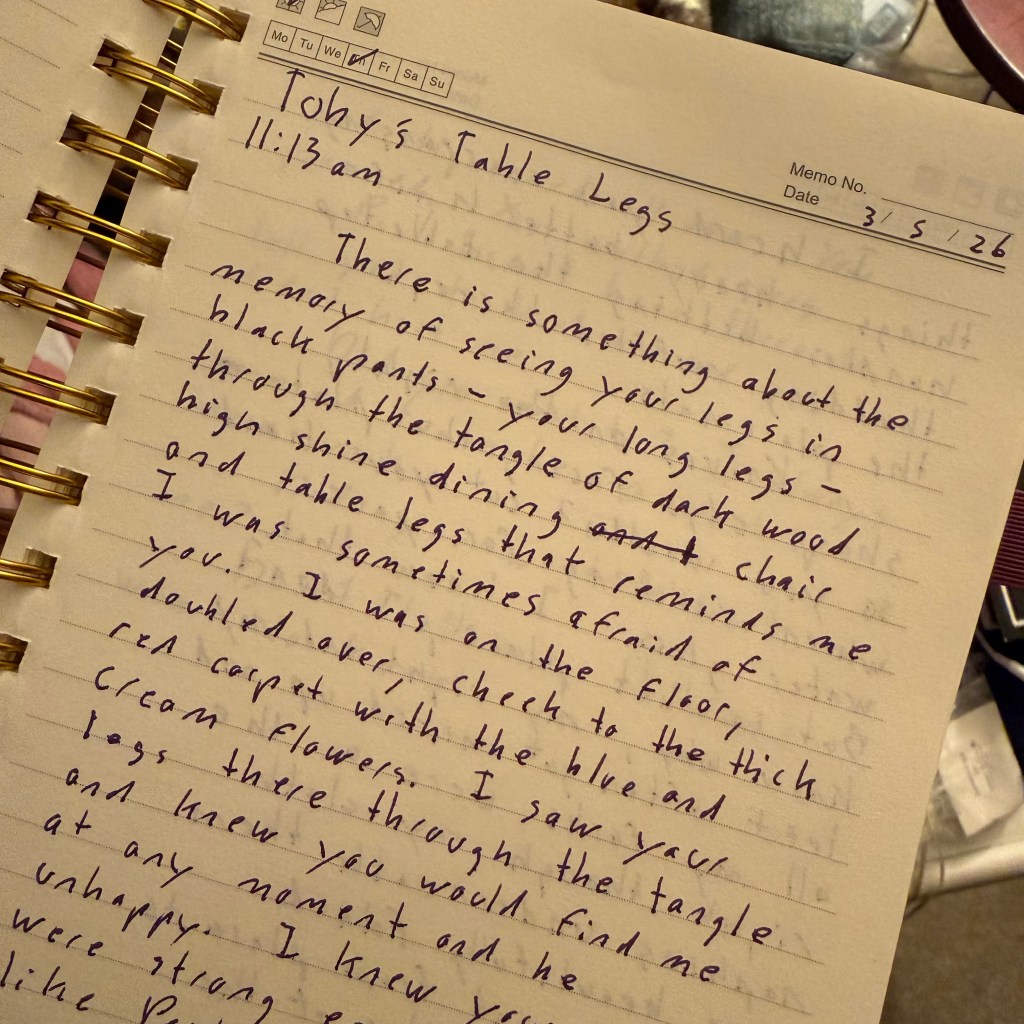

I sat in the wood-paneled study room in college with my left hand pressed against my forehead writing short stories longhand for hours as day turned to night, turned to very late night. I’d dance around air-conducting baroque music thinking of what next things my characters should be doing and what most clever ways I could say it.

All through the eight years I was trafficked—even then during that horrendous abuse, I spent so much of my “free” time alone at the keyboard writing endlessly about what was happening to me. I filled countless file folders on my shiny new Gateway computer and more spiral notebooks than I could ever keep track of. Words words words as Shakespeare would say. They didn’t always make sense during that time, but they kept me anchored to something, even if it was just my own hands moving, the click of the keys, the scratch of the pen, the flick of one page to the next.

I went to the Iowa Summer Writers’ Workshop twice and found my joy and my people. I didn’t bring an essay for class. I wrote it while I was there. I stayed up late in my hotel room writing it. I dashed into the college computer lab the day it was my turn to be workshopped, typed it out at emergency speed, and ran in to class with my ten copies, wet ink drying on my fingers.

And after I survived the trafficking, while I was barely surviving survival, when I was desperately poor and living in an apartment that had roaches in the dishwasher, when I was working at Walmart and smoking with old Southern ladies and bitching about customers, managers, and my swollen feet, I never stopped writing. I started a blog about my Walmart experiences. I started a blog about world spirituality. I started a blog about my burgeoning Paganism. I started a blog about 12 step recovery. I started a blog about tarot. I started this blog. I started more blogs. I started a blog… I started a blog… I started a blog…

And now, twenty years after the trafficking ended and nearly forty years after I wrote my first poem, and probably over fifty blog starts later, I am still writing. And I am reading Writing Down the Bones and realizing for the first time, after all this time, that I am a writer. I am a writer all the way down to my bones and always have been. I am a writer the way Angel is a drummer. I am a writer the way Natalie Goldberg is a writer.

It’s how I make my way in the world. It always has been whether I wanted it to be or not. My passion for the written word has burned for decades in spite of myself.

I wonder what will happen when I embrace its burning as myself.

My very own self.

We shall see.

-M. Ashley