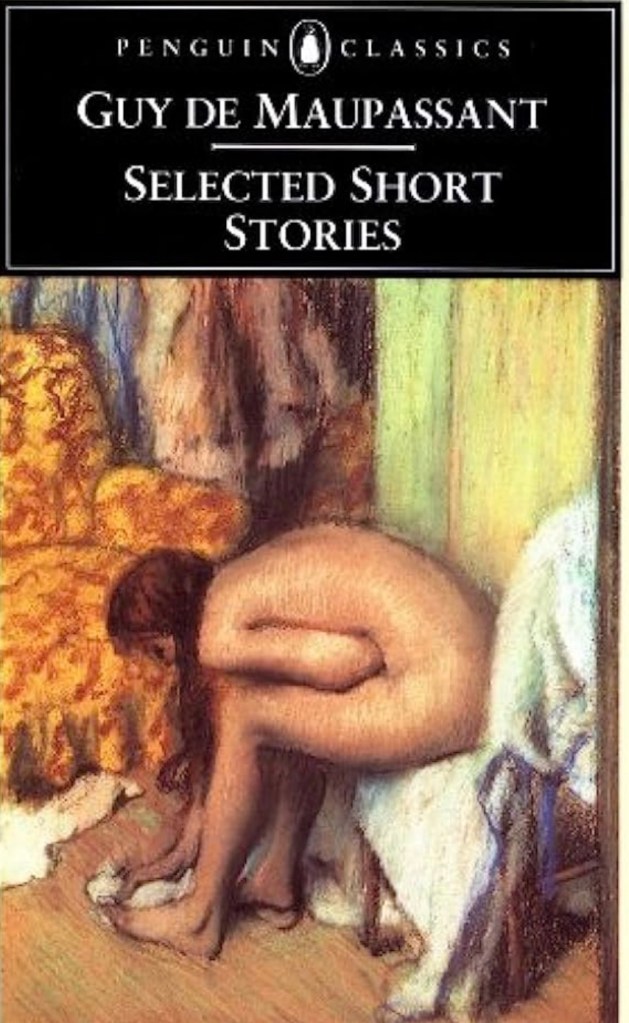

I have a book of Guy du Maupassant stories. On the cover is an impressionist painting of a woman coming out of the bath and drying her feet. I assume it’s by Degas because he’s the impressionist I did my high school French class report on and, as far as I’m concerned, all impressionist paintings that aren’t famously and obviously by some other painter, were painted by Degas.

Degas started going blind at the end of his career. Tragedy. Tragedy for him and for us. I am legally blind. The tragedy is merely personal. The world does not mourn a loss over the fact that reading, for me, is slow and difficult. I have to be choosy about what I read because it takes so much time and effort. In college, I chose to read that book of Maupassant stories. After college, I chose to read it three more times.

Those stories can be a little like Far Side cartoons. Sometimes you don’t get it on your first shot. Sometimes you need someone to explain the world and the ending to you.

My junior year of college, I had a little time between this and that, who knows—I don’t remember the obligations, I only remember the time in between. There was an in between place on the Vanderbilt campus where four paths met in a sort of pedestrian roundabout. At the center of the circle was a planter overflowing with the campus’ signature Spring yellow tulips. At the center of the planter was a blossoming dogwood, shedding its white blossoms, covering the ground in floral snow. The circle was bordered by ancient shade trees and magnolias. There were antique style street lamps dotted around. At night, they cast pale blue efficiency light. There were glossy wooden benches.

I was alone in the circle, in the in between time, in the in between place, sitting on one of the glossy benches. I was reading Guy du Maupassant. It was a bliss time. A life is only blessed with so many, and this was a precious one of mine.

I read a story about a man who observes another man’s gaudy, worldly treasures and also his beautiful daughter and wife. That’s the whole of the story—the observations of the one man and the bragging of the other on all his gaudy, worldly possessions. It’s the kind of story that, when it ends, you flip the pages expecting another ending and find only the beginning of another story. Maybe the printer made a mistake.

I stood up from my glossy bench, chewing on it. I went to my other obligation. I went back to my dorm room overstuffed with the detritus of a busy college career. I called my mom.

I told my mom about the story and asked her what she thought it meant. She said it was quite obvious, wasn’t it? The treasure was the women. In all that house full of stuff, (I looked around my own room and was embarrassed), in that house full of stuff,, (I thought about how often I had walked through that in between place circle with its gold tulips and dogwood snow and ignored it on my way from stuff-to-do to other stuff-to-do and was embarrassed), in that house full of stuff, the women were the treasure. The family bond was the most precious thing,

I thought about how often I neglected to call home in favor of some seemingly more pressing or interesting stuff. I was embarrassed. My life was stuffed with such stuff.

I told my mom I got it now. I told my mom she was an epiphany. I asked her how her day had gone.

-M. Ashley